There are many articles on the internet these days on what schools should and shouldn’t be doing. Often these articles are more like a list of strongly worded rules with a short, superficial explanations, with claims that their conclusions fit all classroom situations and contexts. For example, this article, which states that weekly spelling tests should be abandoned.

Perhaps if these articles were just shared with other teachers in public schools in English speaking countries, this would be appropriate. However, recently I have seen many teachers taking these articles and claiming that the conclusions also apply to Japanese EFL students. While this might be true on occasion, it is very important to remember that children in English speaking countries learning English have a lot more English input than an EFL student in Japan learning English once a week in a private language school.

While I was doing my dissertation, I noticed that there was a real lack of research about children who were learning English as a second language. Therefore, I had no choice but to use research done on children who were living in an English speaking country, usually American children. To my surprise, findings of my own action research on my own students often times contradicted those of research done on children in America.

When I first started BIG BOW, we had a large number of returnee students who had returned to Japan at the age of 7 or 8. They wanted to write about their own ideas in English, but had trouble doing so because they did not spell words correctly and instead wrote the words as they thought they should be spelled. As a result, I often had to read their work aloud to help me figure out the words they wrote. This was fine when they were young, but by the time they reached 9 or 10 years old, they were embarrassed about their spelling errors and became reluctant writers. Something needed to be done, but I wanted working on spelling skills to be a positive experience with the goal of making writing easier for students.

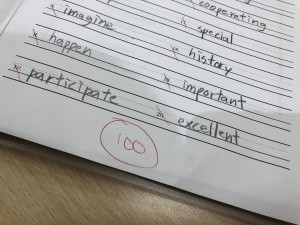

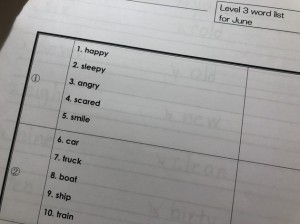

I used the Cambridge YLE word lists to create different levels of core spelling words that students should know, in order to be able to write on a basic level. Students were given 20 words to learn for an end of month test, ten new words and ten words for review. Each student was given a word list at their own level and told repeatedly they were only competing against themselves. Only students in elementary school were given spelling tests. In the beginning, some students were very eager to try this and some students were reluctant, but in the end most students got used to the tests. After a year, we began to see results. Writing assignments and “free writing” projects started going a lot more smoothly because students now had basic spelling skills.

We’ve been giving spelling tests for over 10 years now and have tweaked it here and there over the years. The spelling tests have evolved to the point where some younger elementary students start off with only three words per month, so we can gently begin to learn to spell. Students are given small prizes for consistently scoring well on tests, but students still know they are only competing against themselves. Most importantly, as writing in English becomes more and more important in Japan, my students are prepared for the future.